Cyclically parallelized Treecode for Fast Computations of Electrostatic In teractions on Molecular Surfaces

treecode, electrostatics, parallel computing, MPI, load balancing

We study the parallelization of a flexible order Cartesian treecode algorithm for evaluating electrostatic potentials of charged particle systems in which \(N\) particles are located on the molecular surfaces of biomolecules such as proteins. When the well-separated condition is satisfied, the treecode algorithm uses a far-field Taylor expansion to compute \({O}(N\log{N})\) particle-cluster interactions to replace the \({O}(N^2)\) particle-particle interactions. The algorithm is implemented using the Message Passing Interface (MPI) standard by creating identical tree structures in the memory of each task for concurrent computing. We design a cyclic order scheme to uniformly distribute spatially-closed target particles to all available tasks, which significantly improves parallel load balancing. We also investigate the parallel efficiency subject to treecode parameters such as Taylor expansion order \(p\), maximum particles per leaf \(N_0\), and maximum acceptance criterion \(\theta\). This cyclically parallelized treecode can solve interactions among up to tens of millions of particles. However, if the problem size exceeds the memory limit of each task, a scalable domain decomposition (DD) parallelized treecode using an orthogonal recursive bisection (ORB) tree can be used instead. In addition to efficiently computing the \(N\)-body problem of charged particles, our approach can potentially accelerate GMRES iterations for solving the boundary integral Poisson-Boltzmann equation.

MPI-based parallelization

1 on the main task:

2 read protein geometry data (atom locations)

3 generate triangulation, and assign particles at triangle centroids with unit charges

4 copy particle locations to all other tasks

5 on each task:

6 build local copy of tree and compute moments

7 compute assigned segment/group of source terms by direct sum

8 compute assigned segment/group of particle-cluster interaction by treecode

9 copy result to the main task

10 on the main task:

11 add segments/groups of all interactions and output result

The treecode method requires low \(O(N)\) memory usage, and our focus is on computing interactions between induced charges on triangular elements characterizing molecular surfaces. We therefore store an identical copy of the entire tree on each MPI task (even for very large systems), permitting the application of a simple replicated data algorithm. Assuming that each MPI task has 24GB of available memory, our parallel algorithm can handle interactions between about 20 million charged particles, which is more than needed in this biological scenario. However, we note that for some three-dimensional applications, e.g.~in astrophysics, which have much larger numbers of particles, this approach of tree replication will rapidly limit scalability. To this end, we can alternatively apply a scalable domain decomposition (DD) parallelized treecode using an orthogonal recursive bisection (ORB) tree. Numerical results using both treecode parallelization strategies are provided for comparison.

In treecode, we loop over target particles, and each particle can be treated as an independent interaction with the tree, whose copies are available on every task. Hence our implementation divides the particle array into \(n_p\) segments (for the sequential scheme, see below) or groups (for the cyclic scheme, see below) of size \(N/n_p\), where \(n_p\) is the number of tasks, and the segments/groups are processed concurrently. The pseudocode is shown in above table. Communications are handled using the MPI_Allreduce routine with the MPI_SUM reduction operation

Optimal load balancing

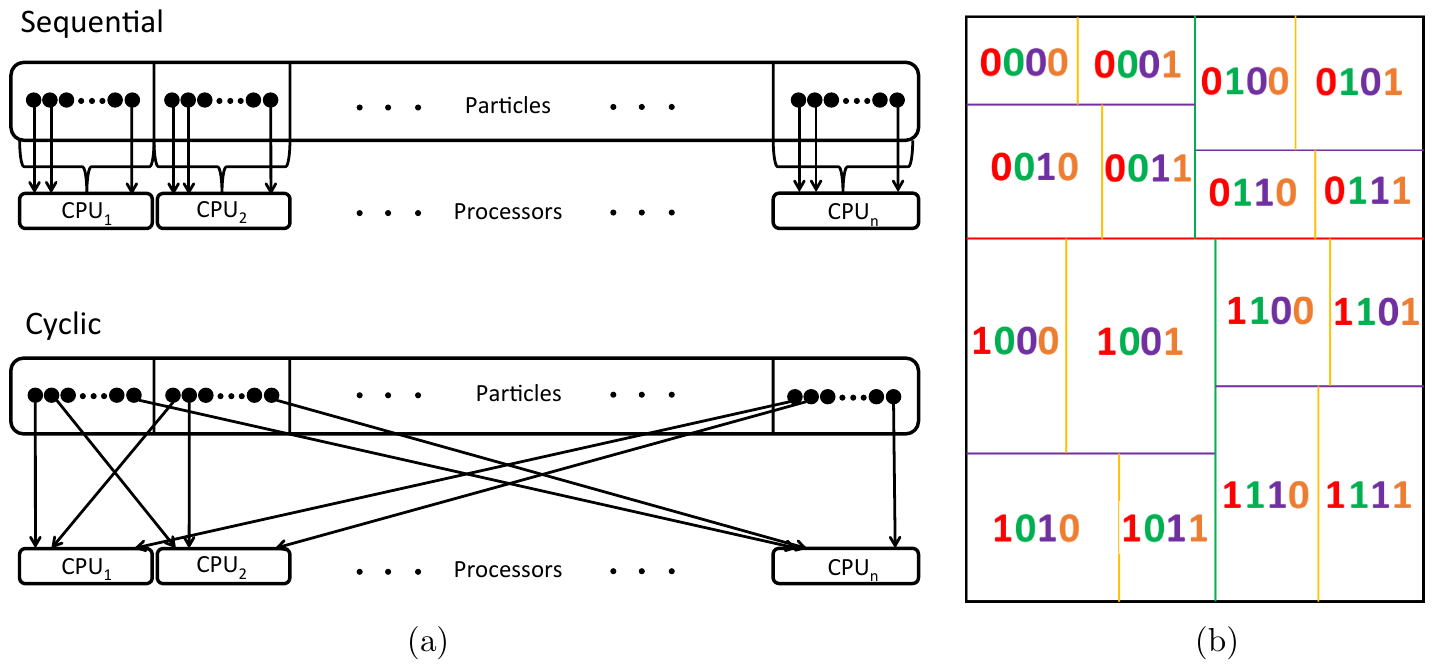

The initial and intuitive method to assign target particles to tasks is to use sequential ordering, in which the 1st task handles the first \(N/n_p\) particles in a consecutive segment, the 2nd task handles the next \(N/n_p\) particles, etc. The illustration of this job assignment is shown in the top of the above figure (a). However, when examining the resulting CPU time on each task, we noticed starkly different times on each task, indicating a severe load imbalance. This may be understood by the fact that for particles at different locations, the types of interactions with the other particles through the tree can vary. For example, a particle with only a few close neighbors uses more particle-cluster interactions than particle-particle interactions, thus requiring less CPU time than a particle with many close neighbors. We also notice that for particles that are nearby one another, their interactions with other particles, either by particle-particle interaction or particle-cluster interaction, are quite similar, so some consecutive segments ended up computing many more particle-particle interactions than others that were instead dominated by particle-cluster interactions. Based on these observations, we designed a cyclic ordering scheme, as illustrated on the bottom of the above figure (a) to improve load balancing. In this scheme, particles nearby one another are uniformly distributed to different tasks. For example, for a group of particles close to each other, the first particle is handled by the first task, the second particle is handled by the second task, etc. The cycle repeats starting from the \((n_p+1)\)-th particle. The numerical results that follow demonstrate the significantly improved load balance from this simple scheme. We note that we also tried other approaches, such as using random numbers to assign particles to tasks, but these did not result in as significant improvements as the cyclic approach.

Domain decomposition parallelized Treecode

The cyclically parallelized treecode algorithm has two significant advantages: easy implementation and high parallel efficiency. However, due to the fact that the entire tree is built on each task, the scale of the problem this algorithm can handle is limited by the memory capacity associated to each task. As a remedy, for very large problems beyond this memory limit, we implement a Domain Decomposition (DD) parallelized treecode under the framework of the orthogonal recursive bisection (ORB) tree from Salmon’s thesis, whose open source C++ implementation using the 0th moment (center of mass) is contributed by Barkman and Lin. Here we briefly describe the DD-parallelized treecode using the ORB tree structure.

Starting from one rectangular domain containing all particles, the ORB treecode algorithm recursively divides particles into two equal amounts of groups by splitting the domain using an orthogonal hyperplane (perpendicular to the longest dimension of the domain) until the finest level in which the number of tasks equals the number of subdomains at that level as illustrated in the above figure (b). In this manner, each task, as loaded with the same number of particles, is associated to a subdomain and has a partner task (illustrated as the 0-1 difference using the same color in their binary code) at each level of the ORB tree division. Once the ORB tree is constructed, each task builds a local B-H tree based on their loaded particles, and communicates with its partner task at each level to exchange additional tree structure information such as clusters and their moments. Here cluster information is sent only when the maximum acceptance criteria (MAC) between particles of the receiving task and clusters on the sending task is satisfied. After this procedure each task stores only a small part of the entire tree such that the far fields are seen only at a coarse level while near fields are seen down to the leaves, as controlled by the MAC. Note that such a “local essential tree” is a subset of the full tree and is the necessary tree structure information for computing interactions between the task’s loaded particles and the entire tree. This is the major difference from the cyclically parallelized treecode in which the entire tree is built in the memory of each task. The details of constructing the ORB tree can be found in link and our new and additional contribution is to implement the it arbitrary order Taylor expansion as opposed to the original 0th order (center of mass) expansion. In updating the moments for lower levels of (larger) clusters using moments from higher levels of (smaller) clusters, a moments to moments (MtM) transformation as described in is applied.

Reference: https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0010465520303672